Our Collective Noise (OCN) is a research-based tactical media project. As an attempt to transform the top-down pervasive qualities of machine learning (ML), computer vision (CV), and surveillance technologies into a bottom-up tactical tool, it plays around the concepts of noise, de-identification, accidental aesthetics, and human-machine collaboration. OCN, as an offline system, uses live webcam feed, ML, and CV to detect people and simultaneously turn them into coarse pixels to replace the common aim of precise identification in surveillance technologies with anonymity. Coarse pixels are constantly stitched together to create collective abstract human-machine interaction patterns that people are collectively and unidentifiably part of. In a world where thriving ML, CV, and AI (artificial intelligence) technologies increasingly rely on cleaner datasets, higher processing capacities, precise labels and categories, OCN turns the technology against itself, in pursuit of revealing the latent potential in noise, anonymity, and collective action.

tactical media, counter-surveillance, poor image, noise, pixel, accidental aesthetics

Pattern recognition lies at the core of machine learning (ML) practices. Object detection practices powered by computer vision (CV) aim for precise pattern recognition, categorisation, and identification of bodies of matter. Often, pattern recognition activities of ML and CV take an extractivist form when approaching data as a resource and an intrusive form as part of surveillance and tracking technologies in the everyday. They operate as top-down tools, utilised by governments and companies under claims of safety or for economic benefit. Against the grain of such use, tactical approaches to object detection can subvert who controls the technology and who is placed on the detected end.

According to Michel de Certeau (1974), the dynamics of everyday life, in which the humans are forced to act as passive consumers and users, is determined by the tension between strategies and tactics. While strategies signify top-down decisions imposed upon everyday people by power-holding institutions, tactics are employed by those people to subvert and re-appropriate top-down technologies, products, and discourses to turn them into individual resistance mechanisms.

Influenced by the tactical framework de Certeau drew, 90s witnessed the emergence of a research and artistic field dubbed the Tactical Media. According to David Garcia and Geert Lovink (1997), tactical media signifies a qualified form of humanism and provides “an antidote to newly emerging forms of technocratic scientism which under the banner of post-humanism tend to restrict discussions of human use and social reception.”

As a contemporary example of a tactical media that deals with surveillance and computer vision, Dries Depoorter’s The Flemish Scrollers (2021–2025) places political figures under the public’s gaze by using the live streamed sessions of the Flemish Parliament in Belgium to automatically detect members of the parliament who are distracted with their smartphones, warning them by posting their distracted moments on social media. On the other hand, Paolo Cirio’s Capture (2020) reverses surveillance dynamics by targeting French police officers. By collecting 1000 public photos of police from protests and using facial recognition to extract 4000 individual faces, Cirio created an online database for crowdsourced identification of the officers by name.

Depoorter and Cirio’s works, through their ability to turn the direction of the surveillance around, shifts the power dynamic by entrusting ordinary people with the ability to gaze upon decision-makers and law-enforcers, inverting the technology's often pervasive surveillance function and transforming it into a tool that induces accountability and visibility.

The work presented here, Our Collective Noise (OCN), seeks to challenge the typical objective of precise identification in object detection to explore the aesthetic possibilities of de-identification, in other words, rendering people anonymous to algorithmic surveillance. By abstracting people through coarse pixelation, OCN strives for human-machine interaction patterns that people are collectively and unidentifiably part of.

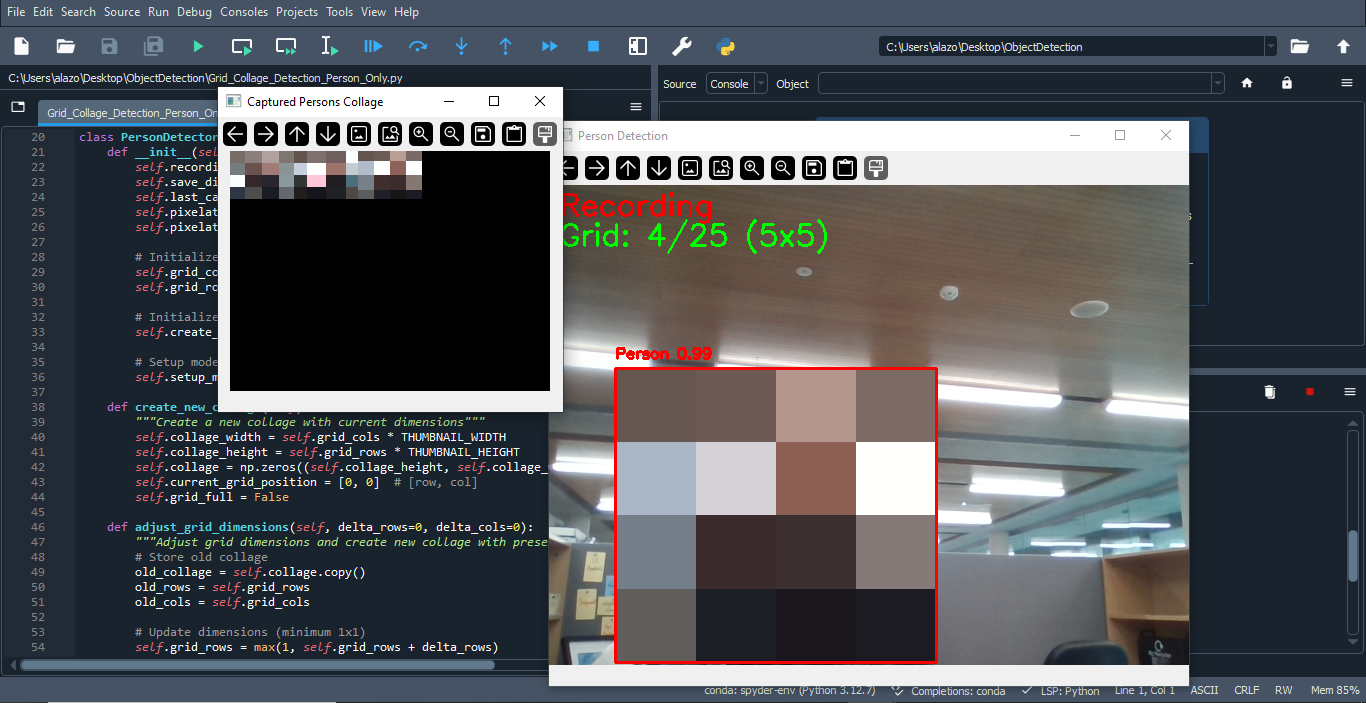

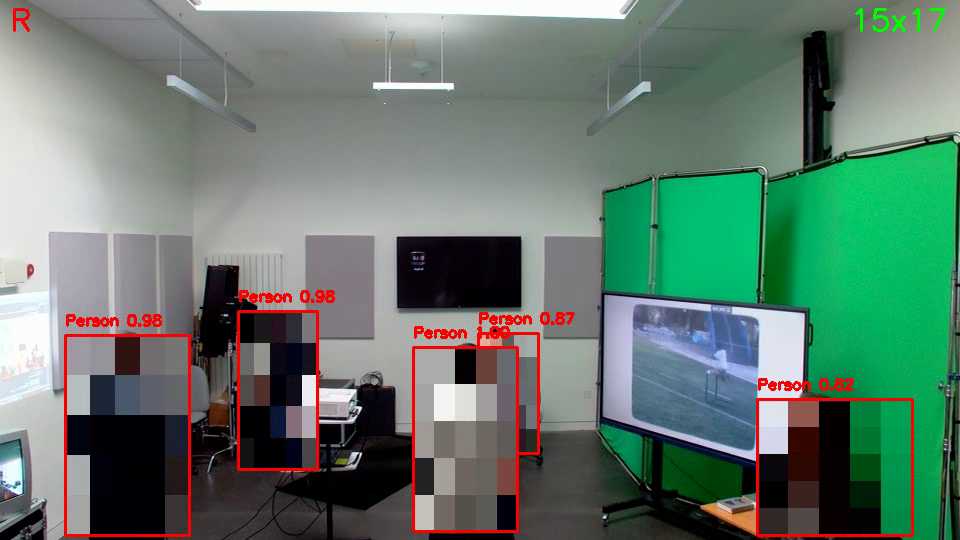

To achieve this, an application that processes the live webcam feed to detect objects in real-time is put together. The application uses the YOLO (You Only Look Once) model, pre-trained on the COCO (Common Objects in Context) dataset, which contains labelled images of 80 common objects. The model analyses each video frame from the webcam to identify objects including people. OpenCV (Open-Source Computer Vision Library) is used to capture the webcam feed, process the video frames, and integrate with the YOLO model.

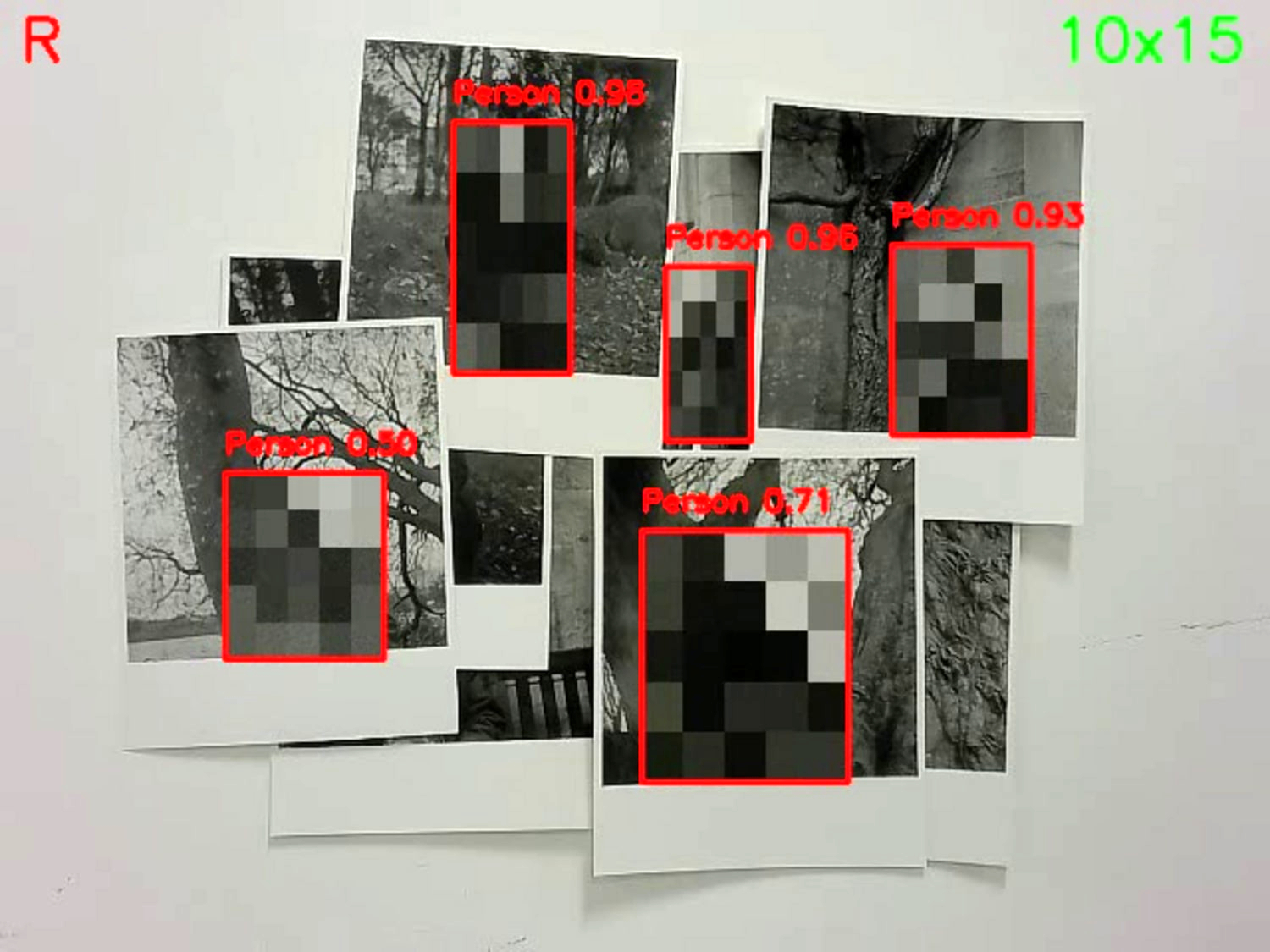

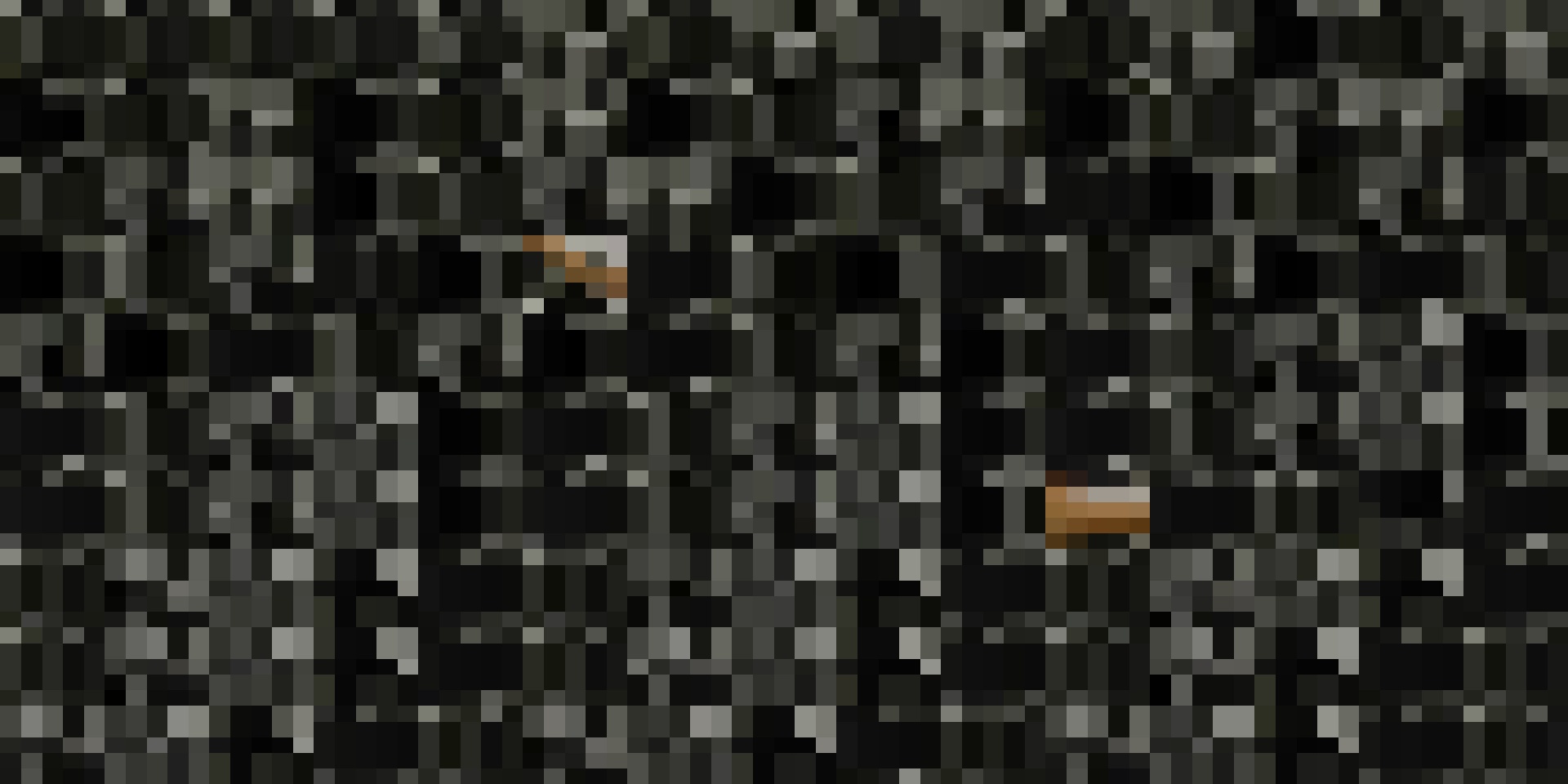

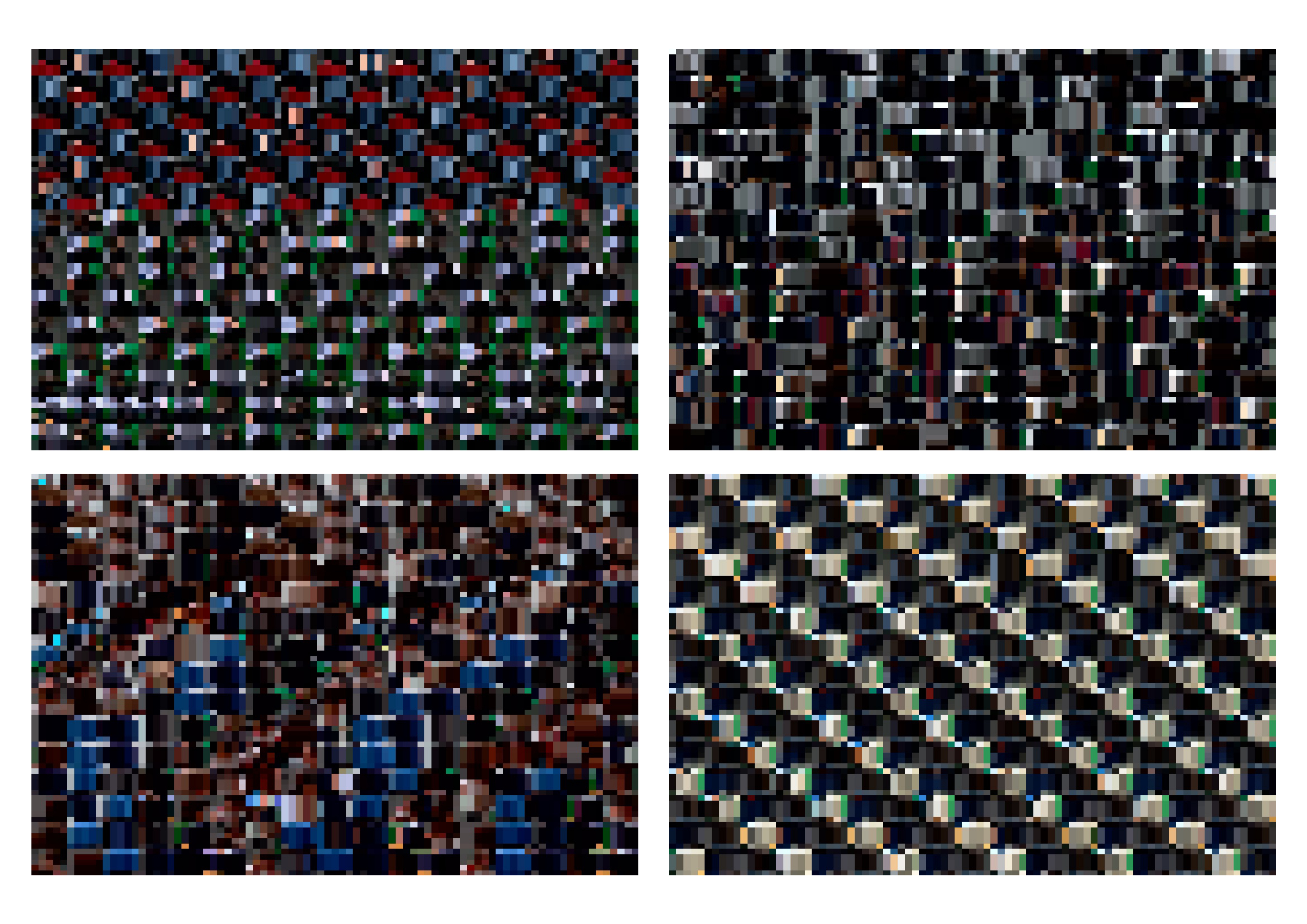

These components work together to create a system that detects objects in real-time. The code is then tweaked to detect only people and simultaneously anonymise them through pixelation. At set intervals, snapshots of each detected and pixelated individual are captured and added to an adjustable grid, forming an image collage. The collage is automatically saved once the grid is full, and the process starts over again. The emerging visuals manifest as abstract tapestries of the continuous dialogue between computer vision and human presence.

Tim Barker (2011, 43) describes the artist in human-machine collaboration as someone who engages in a dialogue with the machine, establishing a framework of constraints within which the system operates, guiding but not directly creating the outcome. The machinic system becomes an intermediary between the artist and the artwork, enabling unexpected results to surface. In OCN, computer vision departs from precision, identification, and from the programmer/artist’s total control to act as a facilitator to lead the way to the unforeseen. As more individuals engage with computer vision, the system's output noise becomes increasingly unpredictable, generating an ongoing stream of spontaneous human-machine interaction patterns.

OCN also acts a response against the new form of image-making through denoising encountered in diffusion models. These models start with complete noise and by iterative denoising reach clear, intelligible, and statistically significant images. Hito Steyerl refers to these types of images mean as they result from statistical distribution and averaging but also built on black-boxed infrastructures of precarity, social inequality, and extraction (Steyerl 2023, 84).

Precise pattern recognition and labelling play an important role in the training of diffusion models so that they can imitate existing modes of representation with minimum quirks. In contrast, OCN embraces noise, unintelligibility, and statistical insignificance1 as aesthetic qualities, intentionally producing dirty or poor data by contrasting the typical ML preference for data cleanliness and richness. Paradoxically, with its integration of open access models and libraries such as YOLO, COCO and OpenCV, OCN relies on clear, intelligible, and correctly labelled images in its attempt to rebel against them. For OCN to de-identify people, it needs to clearly identify them first.

According to Martin Zeilinger tactical forms of AI are “likely to resist strategic approaches that blackbox knowledge, restrict access, or reinforce narrow conceptualizations of agency” (2021, 51). This is where OCN’s claim as a tactical work comes into play. It uses ML and CV to strip extractivist, pervasive, and exclusive applications of surveillance away to introduce open-source availability and right to stay anonymous in face of machine visions.

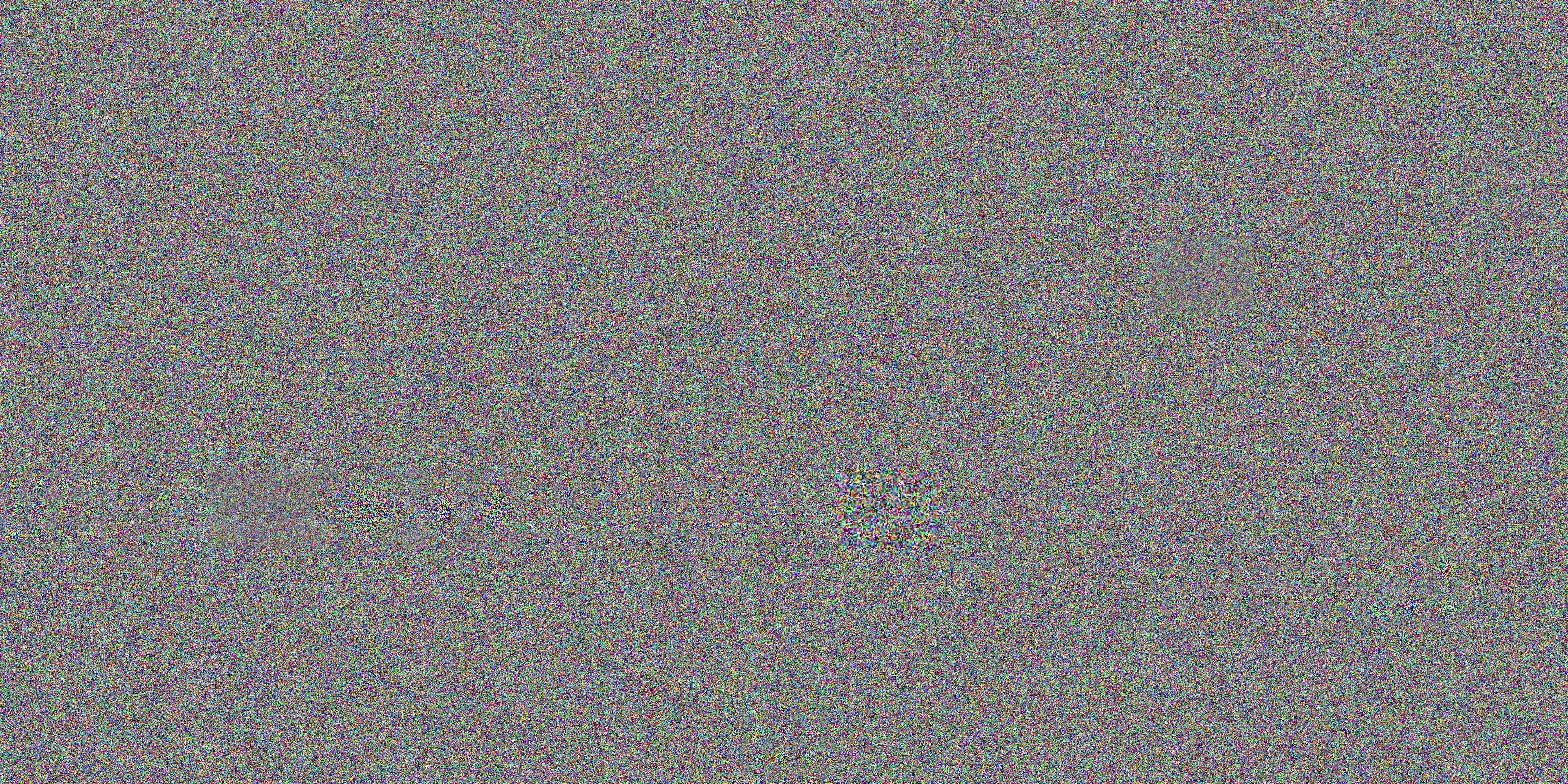

While developing OCN, I also experimented with the Gaussian noise instead to coarse pixels, as an attempt to play around the process of denoising in diffusion by re-noising clear images. In the end, I found Gaussian noise too noisy. In my attempt to generate noise and unintelligibility, I was still interested in seeing certain recognisable traces from the source images like colours and lighting transferred into pixels. In Gaussian noise, these characteristics were all wiped out to create pure noise. Discarding Gaussian noise, I returned to pixels.

OCN finds one of its conceptual and practical roots in glitch art which emerged as a reaction to strict encounters with art and media technologies by cultivating unforeseen, unwanted, and disregarded media artifacts as a new form of media art criticism. Even though, with pre-formulated approaches and recipes, a branch of glitch art has taken the form of a more normative creative practice, it still consists of widely dispersed, aesthetically multivariate, and critically widespread approaches.

I am reserved to categorise OCN as glitch art, but glitch theory proves quite helpful in situating OCN in the context of digital media research and practice. In Glitch Moment(um), Rosa Menkman, after a detailed discussion of glitches and an attempt to categorise them, concludes that the fluidity of such artifacts encountered in human-machine interaction makes glitch art almost undefinable. At the intersection of informatics, media, cultural studies, and art, glitch signifies a wide possibility of post-procedural expressions that go against the grain of linear and quantifiable approaches by departing from well-defined and confined practices of art (Menkman 2011, 34).

By defining glitch art as post-procedural, Menkman highlights that glitch artifacts could only become art after they emerge as technical accidents and are subsequently put into a distinct cultural context to amplify their aesthetic and critical potential. Glitch art signifies a deliberate curation of media failures.

Menkman’s discussion of the glitch starts with an attempt to categorise noise artifacts encountered in machine communication. Drawing from Claude Shannon’s remarks on noise, Menkman initially determines three categories for noise artifacts: encoding/decoding, feedback, and glitch artifacts. In Shannon’s theory, noise manifests itself as either an internal or an external force that disrupts an otherwise well-functioning system (Menkman 2011, 13). By obscuring the message on its way from point A to point B, noise creates ambiguity in communication.

Menkman argues that when the source of such disruption is known, it is classified either an encoding/decoding or feedback artifact. If the source of the noise remains unidentified, then it gains the status of a glitch artifact. However, these classifications are fluid and depend on the observer’s ability to detect the source of such artifacts. Due to their versatile nature, glitch artifacts can be seen as entirely overlapping with noise artifacts or a subset of them.

OCN is concerned with creating a system where disruption of the message is embraced as the foremost aesthetic and critical tactic. While the commonplace aim –or the intended message– of algorithmic detection is precise identification of bodies, the disruption of this message is achieved by rendering bodies unidentifiable. The system transforms crisp images into what Hito Steyerl calls poor images (2009) that are low in resolution and often neglected as they fail to deliver clarity and high-resolution which have become typical denominators of contemporary image quality. Poor image helps us think about what an image is supposed to be and what an image could be. How elaborate the resolution should be for something to be considered an image? Could a single pixel be an image?

The disruption of the message in OCN is a purposeful, coded intervention that aims to create images with emphasised poor qualities. It is not an unexpected nor unintended interference in the communication channel in the sense Shannon talks about noise but is the core intended communicative mechanism. This raises a question about the OCN’s relationship to noise and glitch art: can deliberate, systemised degradation still be considered noise as part of artistic expression?

I believe the answer is “yes” and it encompasses several reasons. First, the poor image comes with a cultural significance. In the age where visual technologies are defined by ever-increasing image resolutions, mega-pixels, AI-assisted image enhancements, photorealism, large-size documents, and equally large processing capacities, coarse pixels, images that lack detail, images that are almost frictionless within my computer’s storage space (kilobytes), and images that are primitive2 in every commercial sense of the word disrupt a broader system of values and understandings.

Second, OCN is a post-procedural work that appropriates low resolution as its main critical and aesthetic feature. It employs coarse pixels as tactics for visual compression to weave digital tapestries that foregrounds, as Eryk Salvaggio put it, “the overwhelming complexity of the world.” Potentially, the closest way we can represent the complexity of the world is not through practices of clear-cut labelling, categorisation, and intelligible images but by weaving together pieces of unintelligibility to create noise:

Order can lean into overdetermination, this reliance on categories, systems, and labels that limits possibility. A kind of structural mechanics gets imposed that is resistant not only to change, but the shift of perspective that instigates change. Order requires that, whereas noise challenges that. The thing is, is that all order deteriorates, whether we love the world we've made or not. Nothing freezes still. (Salvaggio November 2024)

Deliberate integration of elements previously deemed mistakes or failures into artistic expression finds its roots in 19th-century Impressionism, transforming assumed errors of execution and subject matter into deliberate aesthetic and professional techniques. The transformation of the error “from a mark of scorn to a mark of ambition” (Roberts 2011, 212) signifies the opening of a new path in artistic expression that challenges norms while, over time, creating new ones. In the contemporary context, by treating noise artifacts as the main focus of their creative investigation and expression, glitch artists shift the focus from clear-cut and pre-determined outputs to processes that fail and produce unpredictability.

It is important to note that glitch/noise art is not subject to complete chaos. As with other creative practices that appropriate errors, failures, and accidents, glitch/noise art involves negotiating unpredictability with controllability. Cases where the balance leans too heavily towards controllability to consistently create outputs that aesthetically look appealing tend to result in, what Rosa Menkman calls “conservative glitch art,” that lacks critical edge and subversiveness:

This ‘new’ form of conservative glitch art puts an emphasis on design and end products, rather than on the post-procedural and political breaking of flows. There is an obvious critique here: to design a glitch means to domesticate it. When the glitch becomes domesticated into a desired process, controlled by a tool, or technology – essentially cultivated – it has lost the radical basis of its enchantment and becomes predictable. It is no longer a break from a flow within a technology, but instead a form of craft […] what was once a glitch is now a new commodity. (Menkman 2011, 55)

Glitch art constantly threads the thin line between curating glitch artifacts and turning them into a commodities. As I was scrolling through the overstimulating realm of Instagram, I encountered an ad by an account named glitchwerks for its Black Friday sale:

BLACK FRIDAY SALE 15% OFF ALL ORDERS

DISCOUNT APPLIED AT CHECKOUT

Due to our sandblaster being down all digicams will come in original manufacturers paint job in order to ensure an arrival before the end of December!

Also sharing technical information about their digicams, glitchwerks was prompting users to buy their product: “$325 shipped, DM us to claim it!” As Menkman claimed, this kind of work “reduce[s] the glitch to an imagistic slogan: ‘No Content – Just Imperfection’” (2011, 50).

Michel de Certeau introduced the concepts of strategies and tactics as main determinants of everyday experiences in The Practice of Everyday Life (1974). In de Certeau’s framework, strategies refer to the top-down, institutional efforts to dictate, organise, and control behaviour patterns, while tactics refer to creative re-appropriation and subversion attempts, often informal and outside-the-box actions of individuals to navigate and resist the constraints imposed by institutional power. In the end, the practice of everyday life is characterised by the tension between institutional strategies and individual tactics.

The institutional imposition takes place through the consumption practices of the public. A strategy assumes the individual (or, in de Certeau’s terminology, the user) as a passive consumer that complies with the rigid structure of the offered product, behaviour, or discourse and exhibits a pre-calculated behaviour (1974/1984, xi). However, the individual is not necessarily a passive body waiting to be controlled. As activities of resistance, various tactics are often invented by individuals against the strict impositions of the strategies. The dynamics of everyday life in the contemporary world arise from the friction between the intentions of those in control of production and the individual’s uncooperative attitude towards top-down impositions. The production, as de Certeau uses it, does not only refer to the production of tangible goods but also to the wider production of culture and behaviour.

The desire to highlight creative and critical potentials behind glitch artifacts emerges as a de Certeau-esque tactic against the clear-cut structures and rules of media technologies with specific sub-tactics such as circuit, data, and code-bending. However, as witnessed through the glitchwerks example, the tactics tend to be absorbed and transformed into strategies that do not disrupt but maintain the consumer culture.

John Roberts uses the term systemic antisystemicity (2011, 213) to define art practices that emerge as subversive attempts to challenge the norms through their adoption of error, failure, and accidents yet ultimately gravitate towards or succumb to systematic structures. At the turn of the 20th century, avant-garde art movements like Impressionism, Dadaism, Surrealism, and the use of ready-made objects in redefined a new role for the artist as a person who champions an identity centred on critical observation, challenging societal conventions, and prioritising concepts and processes over tangible aesthetic outputs. What began as an antisystemic approach to artmaking has ironically turned into a foundational framework for contemporary artistic expression, with the very principles of questioning and subversion now becoming somewhat standardised approaches for creating an artistic identity.

OCN attempts to navigate the balance between controllability-unpredictability and systemicity-antisystemicity. At times, it cannot avoid leaning more on the side of controllability to produce unpredictability. While striving to disrupt the commonplace aim of object detection through de-identification and intentionally implementing poor qualities, it tends to domesticate noise. The decision to use pixels but not Gaussian noise was a deliberate attempt to tame and aestheticise noise. The process of domesticating, controlling, or moderating noise serves as a tactical mechanism for producing unpredictability within a set of constraints.

Within the wide spectrum of complete loss of control and control to the extent of commodification, OCN neither transforms errors into marketable products that can be bought and sold nor completely refrains from taming noise to preserve them as raw and erratic artifacts of the digital wilderness. The core intention of OCN is to bring critique to contemporary technological and societal tendencies that pursue perfection, precision, and expansion, often neglecting the critical potential inherent in technological breakdown. By tactically employing the technologies under critique, OCN seeks to challenge existing paradigms by elevating the status of errant, failed, and accidental artifacts—elements that are typically marginalised or suppressed within mainstream technological practices.

The system put together to create OCN can be seen as a practical inquiry in line with what Vilém Flusser expressed as an apparatus for discovering improbable images. According to Flusser, a camera is an apparatus that consists of an infinite number of possibilities within its program, waiting to be discovered (1983/2000, 37). Even though the possibilities are endless and theoretically inexhaustible, the photographer should attempt to unveil these new possibilities and information regardless (1983/2000, 26).

In pursuit of such Flusserian images, each time OCN is put into motion, it generates improbable images that have never been and never will be once again, forming an accidental aesthetics. OCN generates images not through an operator but through the collective effort of the people’s presence and machine vision’s detection ability which come together to create a field of randomness. Each activation of the system produces a distinct visual configuration that is fundamentally unrepeatable, even though tapestries woven follow an overarching aesthetic quality.

Since the 1990s, Jim Campbell has been embracing the creative potential in what is considered a shortcoming of visual technology: low resolution. Campbell’s work has been in favour of ambiguity produced by a handful of pixels against high resolution that leave no space for the contemplative distance that technological imperfection and simplicity provides.

Ambiguous Icon 2 Fight (2000), a matrix of 8 x 11 (88) pixels made of Red-Green-Blue LEDs shows a blurred video stream of a match between two world boxing champions, while his Portrait of a Portrait of Claude Shannon (2000), made of 12 x 16 (192 pixels) white LEDs, circulates Claude Shannon’s black and white portrait mixed with a sequence of random noise.

Campbell’s work thread the line between transparency and opaqueness by reducing images into fuzzy planes which alter the viewing experience by forcing the audience to squint with an attempt to sharpen the image, take a step forward to investigate each individual pixel and take a step back to see how each point makes up the overall image.

When discussions around photography was highly informed by its technological and ontological transformation with the emergence of digital images, Thomas Ruff’s jpgs emerge in the early 2000s. Ruff’s jpgs explore photography’s shifting ontological qualities –transformation from grain of the film to pixel of the digital image– by deliberately increasing the compression rate and lowering the pixel density to make these artifacts the leading aesthetic focus of the image.

Both Campbell and Ruff's works demonstrate how rudimentary approaches to digital image can offer creative possibilities that challenge state-of-the-art technological specifications. While complex technical processes may underlie their works, both artists deliberately use these tools to contribute to what could be called a primitive aesthetics where the main concern is to draw attention to changing conditions and standards of seeing in relation to technological developments.

As digital images are absorbed into the fabric of daily life, new technological developments take centre stage for critical artistic investigations. With more prevalent issues such as constant tracking and identification of objects and people (or rather objectification of people) through digital means of surveillance, we meet Hito Steyerl’s How Not to Be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File (2013).

Steyerl treats anonymity and invisibility as some of the scarcest commodities in the contemporary age and offers a manual for people who desire to reclaim their invisibility by disappearing from machine and human sights. Some of Steyerl’s proposed methods include to go off screen, pretending you are not there, to camouflage, to live in a gated community or a military zone, to become a woman over fifty, and to become a pixel.

Steyerl's suggestion to become a pixel follows her argument that “whatever is not captured by resolution is invisible.” As digital image resolution standards increase, it becomes increasingly difficult to remain invisible or maintain an unidentifiable presence in the face of surveillance technologies. Following this logic, resorting coarse pixels emerges as a tactic for digital invisibility. Reducing one’s existence into a single or handful of pixels in the digital visual world would mean becoming invisible through lack of information. While lack of information may lead to disinformation and manipulation, alternatively, it could be a tool for disappearance.

In his Performance Surveillance (2023), Leon Butler highlights the presence of CCTV cameras by gaining access to online unsecure cameras and turning their feeds into automated generators of random musical compositions. The use of machine learning and computer vision allows Butler to automate object detection and sound generation processes to create an installation requires no further intervention by the artist once put into motion:

[…] the person in the gallery [is] the conductor because they control the camera feed. They can cycle through nine different cameras. If they're the conductor, then the musicians are the people on camera. Their x and y coordinates generate the sound […] They're kind of an unwitting orchestra. That allowed me to take myself out of it. If there is a conductor and an orchestra, I commissioned the work. (Interview with Leon Butler, December 2024)

Artist as a figure who designs human-machine encounters takes centre stage in Performance Surveillance. Butler sets the stage but leaves who is going to turn up to play and who is going to turn up to conduct to complete chance, taking a step towards accidental aesthetics.

As Rosemary Lee mentions, “the idea of giving over agency or intentionality to a process or machine” was already gaining traction in the early 20th century with Dada and Surrealist automatism: “Dada and Surrealist artists often used sets of instructions as a sort of artistic program to be interpreted or orchestrated, combining systems of rules with elements of randomness or unpredictability” (2024, 109). Today, we see the shift from using one’s body like an automated machine to designing interactions where surveillance and object detection are used for creating abstract musical compositions or pixel tapestries.

As a counter-surveillance measure implemented into an art practice, in Facial Weaponization Suite (2012-2014), Zach Blas creates abstract-shaped digital face masks from aggregated facial data collected from participants. By digitally superimposing these masks onto people’s faces, Blas renders them invisible to facial recognition. While Blas’ work obstructs recognition at the digital level, the invisibility cloak –a pullover printed with trained patterns that suppress the objectness scores of its wearer– designed by the Department of Computer Science at the University of Maryland (2019) and the anti-AI mask –a three piece brass mask that eliminates the distinctive facial feature of the human face– designed by Ewa Nowak (2019) interfere with object detection and facial recognition at the physical level by turning their wearers into non-objects and non-humans in eyes of surveillance algorithms.

OCN is also concerned with mean image-making through data-reliant models and statistical distribution. Mimi Onuoha’s The Library of the Missing Datasets (2016-2022) examines what kind of information does not end up forming datasets which potentially skews ML’s vision of the world. Onuoha presents cabinets filled with empty folders representing datasets that don’t exist, carrying labels such as “publicly available gun trace data,” “amount of phosphorus in prescription medicines,” and “public list of citizens on domestic surveillance lists.”

In Adversarially Evolved Hallucination (2017) series, Trevor Paglen demonstrates that categories and labels necessary for training ML models are inherently problematic due to the ambiguity of concepts we need to deal with as humans. Paglen trains AI models with datasets based on abstract concepts such as Freudian psychoanalysis symbols extracted from Interpretation of Dreams. With the help of a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN), he creates hallucinogenic images that are “entirely synthetic and has no referent in reality, but that the pair of AIs believe are examples of things they’ve been trained to see” (Paglen 2017).

By highlighting the unavailability and rather abstract nature of information, Onuoha's and Paglen’s work show that constructing models of the world through statistical distribution comes with its problems.

The way Paul O’Neill identifies the locations of unmarked Amazon Web Services (AWS) data centres in Ireland by going through planning permissions and satellite records, as well as printing the images of these data centres on postcards (2022, 186) to make invisible infrastructures of resource exploitation visible is a step towards investigative aesthetics.

As Matthew Fuller and Eyal Weizman (2021) coined the term, we are increasingly encountering works of investigative aesthetics that deal with political, social, and environmental conflicts by making use of open-source information that has been kept away from or obscured to the public. The act of accessing and leaking such information is an essential part of investigative aesthetics.

Fuller and Weizman highlight investigation’s commitment to establishing facts from various sources and perspectives. The aim of aesthetic investigations is to assemble “truth claims from a collage of fragments” (2021, 109), advocating that “to uncover the real [one] must make the real” (2021, 110). Aesthetic investigations do not consider truth as a given information but rather as something that should be constructed through collage work of traces left on various bodies of media and materials. Investigative aesthetics is to construct the truth from fragments of information to make it recognisable to an audience.

Besides their tactical nature, many of the works discussed here are investigative. Steyerl and Butler’s works require investigation of surveillance technologies, maybe not a thorough one to establish facts as their end goals but to present subjective and aestheticised version of them. This approach of course has its own dangers of blurring the already ambiguous line between facts and speculations but often artists are confined to partial information to begin with. Perhaps it is precisely this limitation that drives artists to develop affective investigative methodologies that bridge the gap between factual inquiry and creative speculation. A form of investigation, I believe, is also present in OCN.

The title Our Collective Noise has a dual connotation. On one level, it represents noise as a force of disruption that creates unintelligibility. On another level, it signifies a collaborative endeavour that requires collective action to generate ambiguity in the age of data precision.

As far as there is no one detected by the machine, the image seen by the camera stays crystal clear. The noise enters the equation only when the machine starts detecting people. As more people come together to put OCN into motion, the unpredictability and overwhelming complexity of our collective noise becomes increasingly present.

The lack of resolution and presence of noise is a double-edged sword. Invisibility may create a ground for furthering state and corporate violence on those vulnerable. On the other hand, the lack of information may lead to various forms of resistance where surveillance and control technologies are getting increasingly dependent on data.

I want to think that this work disrupts the oppressive and extractivist uses of surveillance and machine vision rather than contributing to them.

As Garcia and Lovink (1997) put it, “tactical media are never perfect, always in becoming.” Although, OCN practically exists, its tactical reach is quite premature. So, I leave a piece of it in your hands. Take its code, deconstruct it, bend it, modify it, hack with it, resist with it, make it your own, and share with others.

Acknowledgements. This paper has taken its current form thanks to the supportive comments of Padraic Killeen, James McDermott, Paul O’Neill, the School of X 2025 cohort and its mentors, particularly Martin Zeilinger, Angela Ferraiolo, Tiago Alves, and Shirley Leung.

Funding for this research is received from the Centre for Creative Technologies, College of Arts, Social Sciences, and Celtic Studies, University of Galway.

Barker, Tim. 2011. “Aesthetics of the Error: Media Art, the Machine, the Unforeseen, and the Errant.” In Error: Glitch, Noise & Jam in New Media Cultures, edited by Mark Nunes, 42–58. New York & London: Continuum.

Blas, Zach. 2012. Facial Weaponization Suite. https://zachblas.info/works/facial-weaponization-suite/.

Butler, Leon. 2023. Performance Surveillance. https://bold.ie/.

———. 2024. Leon Butler Interview by Alaz Okudan.

Campbell, Jim. 2000a. Ambiguous Icon 2 Fight. https://www.jimcampbell.tv/portfolio/low_resolution_works/ambiguous_icon_2_fight/.

———. 2000b. Portrait of a Portrait of Claude Shannon. https://www.jimcampbell.tv/portfolio/low_resolution_works/portrait_of_a_portrait_of_claude_shannon/.

Certeau, Michel de. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life. Vol. 1. Translated by Steven Rendall. Berkeley: University Of California Press.

Cirio, Paolo. 2020. Capture. https://paolocirio.net/work/capture/.

Depoorter, Dries. 2021. The Flemish Scrollers. Dries Depoorter. https://driesdepoorter.be/theflemishscrollers/.

Flusser, Vilém. 2000. Towards a Philosophy of Photography. Translated by Anthony Mathews. London: Reaktion.

Fuller, Matthew, and Eyal Weizman. 2021. Investigative Aesthetics: Conflicts and Commons in the Politics of Truth. London & New York: Verso.

Garcia, David, and Geert Lovink. 1997. “The ABC of Tactical Media.” May 16, 1997. https://www.nettime.org/Lists-Archives/nettime-l-9705/msg00096.html.

Goldstein, Tom. 2019. “Invisibility Cloak.” University of Maryland, Department of Computer Science. November 2, 2019. https://www.cs.umd.edu/~tomg/project/invisible/.

Hitti, Natashah. 2019. “Ewa Nowak’s Anti-AI Mask Protects Wearers from Mass Surveillance.” Dezeen, July 30, 2019. https://www.dezeen.com/2019/07/30/ewa-nowak-anti-ai-mask-protects-wearers-from-mass-surveillance/.

Lee, Rosemary. 2024. Algorithm Image Art. New York & Dresden: Atropos Press.

Menkman, Rosa. 2011. The Glitch Moment(Um). Amsterdam: Institute Of Network Cultures.

O’Neill, Paul. 2022. “Platform Protocol Place: A Practice-Based Study of Critical Media Art Practice (2007-2020).” PhD Thesis. https://doras.dcu.ie/26599/.

Onuoha, Mimi. 2016-2022. The Library of Missing Datasets. https://mimionuoha.com/the-library-of-missing-datasets.

Paglen, Trevor. 2017. Adversarially Evolved Hallucination. https://paglen.studio/2020/04/09/hallucinations/.

Roberts, John. 2011. The Necessity of Errors. London & New York: Verso.

Ruff, Thomas. 2004. jpg Msh01. https://www.moma.org/collection/works/149384.

Salvaggio, Eryk. 2024. “Notes from the Algorithmic Sublime.” Cybernetic Forests. November 24, 2024. https://mail.cyberneticforests.com/notes-from-the-algorithmic-sublime/?ref=cybernetic-forests-newsletter.

Steyerl, Hito. 2009. “In Defense of the Poor Image.” E-Flux. November 2009. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/10/61362/in-defense-of-the-poor-image/.

———. 2013. How Not to Be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File. https://www.artforum.com/video/hito-steyerl-how-not-to-be-seen-a-fucking-didactic-educational-mov-file-2013-165845/.

———. 2023. “Mean Images.” New Left Review, no. 140/141 (April): 82–97. https://newleftreview.org/issues/ii140/articles/hito-steyerl-mean-images.

Zeilinger, Martin. 2021. Tactical Entanglements: AI Art, Creative Agency, and the Limits of Intellectual Property. Lüneburg, Germany: Meson Press. https://meson.press/books/tactical-entanglements/.

The term statistical insignificance is not used in its strict statistical analysis sense (where p-values exceed thresholds of 0.01 or 0.05) but used to highlight how diffusion models generate outputs based on statistical distribution while OCN creates patterns through randomised input that does not comply with such statistical framework. It is this randomisation makes OCN's outputs statistically insignificant.↩

I use the term primitive because the aesthetic qualities I advocate for in OCN are often perceived as remnants of a distant technological past and do not present viable qualities for commercial consumer products today. My use of the term is affirmative as it implies a counter-consumerist and counter-perfectionist position.↩