(Labor) Revealed is a research-based art project in its exploratory phase. Its current iteration is a live performance-based exhibition that explores the impact of AI on creative labor through audience engagement and installations. Visitors to the performance witness a side-by-side comparison of AI and human creativity. The installation will be divided into two sections, where both sides will receive the same creative brief across three disciplines: illustration, musical composition, and sculpture. On one side, an artist will perform the creative labor of executing on a brief while employing traditional non-AI techniques. On the other side, AI tools will be set up, inviting audience members to execute the same brief as the creative professional. The exhibition displays the complete works alongside a timer, showcasing the completion time and revealing the creative labor that went into each work. This juxtaposition aims to reveal the time-value and visual disparity between creative humans and AI labor, contributing to the ongoing discussions around AI’s impact on creative labor practices.

AI and Creative Labor, AI and Creativity, AI human collaboration, Artificial Intelligence, Creative Labor, Immaterial Labor, Creativity and Craft

Artists and creatives have been experimenting with technology in their creative work for a long time. With the recent surge in popularity of artificial intelligence (AI) tooling, we’ve seen an increase in AI being incorporated into art. This leads to an interesting relationship between creativity, craft, and labor when it comes to authorship and how artists and creatives are using AI in their creative practices. A recent photography show at the International Center of Photography (ICP) in New York features the perspectives of three practicing photographers who were invited to create visual pieces of work based on their relationships with AI technology (Katz 2024, Kozanecka 2024). The perspectives of the creative community are reflected in the final exhibition, creating a curated installation that is in conversation with one another where an artist worked solely in with AI—either willfully or feeling as if they need to keep up with trends, while another worked alongside AI as a tool or collaborator, and another intentionally left AI out of their practice. These varying perspectives and approaches are not uncommon in the creative community and in many ways, reflect the diverse opinions and perspectives of the artists and creators who are currently grappling with AI technology today.

In human-AI interactions, some artists are exploring the possibilities of collaborative relationships in practice. For instance, in Sougwen Chung’s creative practice, she trains a robot, D.O.U.G. (Drawing Operations Unit: Generation), with her previous work to explore the human-machine collaboration dynamic. Her live artist output involves live drawing performances, where the robot co-generates new work in real-time (Chung 2015). Chung’s work reflects an era of artists who are co-creating with machines to explore alternative possibilities of work that wouldn’t have been possible in silo, highlighting an area of human-AI interactions that resides in the collaboration space. These artists are interested in the collaborative potential between humans and machines, creating interesting forms of iteration or final outputs that wouldn’t have been possible without one or the other. This collaborative relationship is represented in artists who’ve experimented with GANs (Generative Adversarial Networks), which are generative images created by training on an archive or data (usually the artist’s own), where the artwork also lies in the process of interacting with the models. In Chung’s work, however, she gives autonomy to the machine, yet this autonomy is inherently controlled by her since her drawing partner is trained from her previous drawings.

Not all artists who create with AI do so willingly. Some also do it because they feel the need to keep up with the space, such as those who incorporate AI into their creative practice in the commercial sector, either to stay current and follow trends, or to regain a sense of autonomy when they sense a fear of irrelevance. While commercial and artistic practices differ in their audiences, this fear of irrelevance remains pervasive. In Alexander Reben’s piece, AI Am I? (Reben 2020), Reben creates and crafts a collection of artworks that were conceptually conceived by AI. This conceptual reversal of the previously known relationship between conventional human and technological collaboration is almost an act of resistance, as it surrenders creative control to the machine, highlighting a possible future of loss of autonomy in the creative process. Harry Braverman calls this relationship with technology the “deskilling thesis,” which argues that under capitalism, the tendency to separate concept (creative conception) from execution (craft production) leads to a degradation of workers' skill sets (Braverman 1974). Deskilling can also result in a loss of collective knowledge in craft production, which is integral to the creative industry, as diversity and abundance are essential for creative inspiration.

Creators like Tyler Hobbs and Mario Klingemann, who believe that the art lies in the language surrounding the creation or writing of the code, rather than in the output, typically identify as generative artists working in the generative art space. (Hobbs 2024, 312) (Klingemann 2019) These individuals work with code similar to writing a language, which is widely considered an art form. However, this creates an interesting separation between the human and the machine, as the craft now resides within the machine. Computational art theorist Philip Galanter defines generative art as:

Any art practice where the artist uses a system, such as a set of natural language rules, a computer program, a machine, or other procedural invention, which is set into motion with some degree of autonomy contributing to or resulting in a completed work of art (Galantar 2003).

Generative art highlights an industry and technological response to the increasingly complex relationship between human and machine, as it introduces a diversity of perspectives in the level of human involvement that is needed when it comes to creating art.

Within the creative community, there also exist the resistants whose sentiments align with the Luddites of the 19th century. They are more resistant to and sometimes reject technological advancements that may render their previously valued skill sets useless. This community is represented by those who are part of the Hollywood SAG-AFTRA protest, which opposes the use of AI due to the threat it poses to the livelihoods of writers and performers. (Winter 2023) In a capitalistic society where human value is judged based on the output of our labor, the integration of AI into our current labor practices introduces some friction and resistance. However, in the context of AI technologies, the issue of resistance is a little more complex than just the fear of replacement. There exist complex ethical problems related to copyright infringement, as the core building blocks that create these technologies utilize the uncompensated labor of the exact creative communities it is trying to replace.

Creativity lies at the core of this debate around the use of AI in the creative arts. Although in creative labor practices, there’s a distinction between creativity and craft, where the creative labor is the more elusive cognitive labor, and craft is the execution of the output. Margret Boden describes creativity as “the ability to come up with ideas or artifacts that are new, surprising, and valuable.” (Boden 2004) in which she elaborates through a computational approach, highlighting three distinctive types: combinational, exploratory, and transformational creativity, and its distinction is crucial for evaluating AI's capabilities and their implications for human labor. Combinational creativity is described as bringing together familiar ideas from different subjects in novel ways, exploratory creativity entails discovering ideas within existing conceptual spaces, and transformational creativity involves altering the rules of a conceptual space to make something that was previously impossible, possible. AI systems excel at the first two, but by definition, transformational creativity involves radically altering traditional generative rules, which AI systems are explicitly designed not to do. This creates a technical challenge.

Given that AI models follow algorithmic rules set forth by historical training data, and while they are good at (re)creating things that already exist in the same conceptual space, they generally are not capable of producing radically transformative ideas, which means AI isn’t capable of truly transformative creativity. In our society, transformative creativity is what is truly valued and is what drives change. The diversity and radical differences in transformational creativity lead to the emergence of new art movements. Boden cites Cubism, which transformed our canonical understanding of painting in new ways by visualizing reality through abstract, geometric forms. The loss of transformational creativity can potentially lead to the homogenization of visual culture. As we see more of the same AI work proliferate our cultural landscape, we see an emergence of “AI slop,” which is culturally defined as hollow, emotionless output that is creatively average. Hito Steyerl defines these AI-generated outputs as “mean images,” images that converge to the average that is “hallucinated mediocrity.” (Steyerl 2023) The very nature of generative algorithms’ statistical foundation produces outputs that converge towards the mean, which inherently limits their capacity to generate genuinely original and, therefore, transformatively creative content.

To achieve transformational creativity, one must understand the system and, through this contextual understanding, have the desire and intention to break and bend the rules, introducing new and innovative concepts that may initially not be accepted by society. This cognitive labor, the mental effort required for contextual understanding of the system, is necessary to create creative works that are not only transformative but also emotionally resonant, culturally relevant, and conceptually meaningful. It is the type of creative labor typically performed by a human creator. Maurizio Lazzarato defines this as immaterial labor, which consists of “producing the informational and cultural content of the commodity” (Lazzarato 1996). While type of labor is codified into AI models to artificially create a sense of cultural relevance, without the human creator, there is an absence of emotional resonance and concept in the final output. In other words, a human creator is necessary to drive the direction of transformational creativity, which AI systems are inherently incapable of achieving in isolation.

In the context of automation with AI technology, Matteo Pasquinelli challenges the common understanding of AI systems as anthropomorphic self-thinking technologies by highlighting that

"computation emerged as both the automation of the division of mental labour and the calculus of the costs of such labour” (Pasquinelli 2023).

In other words, AI systems exist because of the of division of labor between the quantification of human cognitive and physical labor and the mechanization of mental practices that is codified in the machine. This calculus of the cost is a measurement that serves as a mechanism for control. This is what makes AI tools inherently an extension of invisible human labor. The automation of mental labor, the work previously done by humans, such as processing and labeling training data and performing logical operations in writing code for the model, remains invisible as we interact with these systems.

What remains visible in the process is the physical implementation of craft in the creative process. In one of the earliest examples of AI programs for artmaking, artist Harold Cohen created AARON in the 1970s. AARON is a series of computational programs written by Cohen to create original artistic images autonomously. This program is then connected to a pen plotter, allowing for real-time creation of these drawings and producing the craft labor required to produce the images (Cohen 1979). The artist, in this context, is producing the creative labor that went into the creation of the concept of the pieces. This collection distinctively highlights the separation between physical and intellectual labor, or creativity and craft, where the machine performs the craft, or physical labor. Craft, as defined by Howard S. Becker, is “a body of knowledge and skill which can be used to provide useful objects” (Becker 1982), representing the technical ability to execute visions or ideas—a function that is within AI's capabilities today. Artists have long utilized technology as a means to produce their work physically. However, as these technologies become increasingly capable of performing more of the intellectual labor, questions arise about how we perceive the value of the end output when AI becomes more involved in the creative process.

Labor (Revealed) is a practice-based research project that explores the relationship between human creativity, AI, and creative labor and questions around the value perception of creative output. The installation is designed as a series of live performances that engage with three disciplines: illustration, musical creation, and physical sculpture. These disciplines are purposely chosen to represent the diversity of different levels of creativity and craft in the creative space, as each may be uniquely affected by AI in various ways.

The design of each installation performance is split into two sides, where both sides will receive the same creative brief. On one side of the exhibition, an AI tool will be set up, inviting audience members to come and execute the brief. On the other side, a creative industry professional will be performing the creative and physical labor of executing on the same brief using non-AI techniques. The final display of work will showcase the end artifacts next to the time to completion. The audience’s work will be shown alongside the creative professional’s work to compare the visual distinctions. This juxtaposition highlights the time-value disparity between creative humans and AI labor, adding to the ongoing debate around AI’s impact on creative jobs. Audience members are invited to debate, critique, and analyze the work outputs, questioning the tradeoff between time and cost, and to visually compare the output of the labor to critically examine what is gained and what is lost by using AI to execute on a creative brief. The disciplines are also purposefully chosen to show a diverse array of crafts and creative industries that are affected by AI, as each industry is affected by AI differently. It intends to question the visibility and invisibility of the immaterial and physical labor involved in the creation of a final visual piece and our relationship with the value perception of each piece.

The arrival of AI tooling is affecting each creative industry at a different pace. Since LLM (Large Language Models) based technology is inherently text-based, research on text and image generation models is inherently more mature than that of musical or sculptural generation models. This means that the landscape of commercially available AI tools for text and image generation is more widely available to artists and creators.

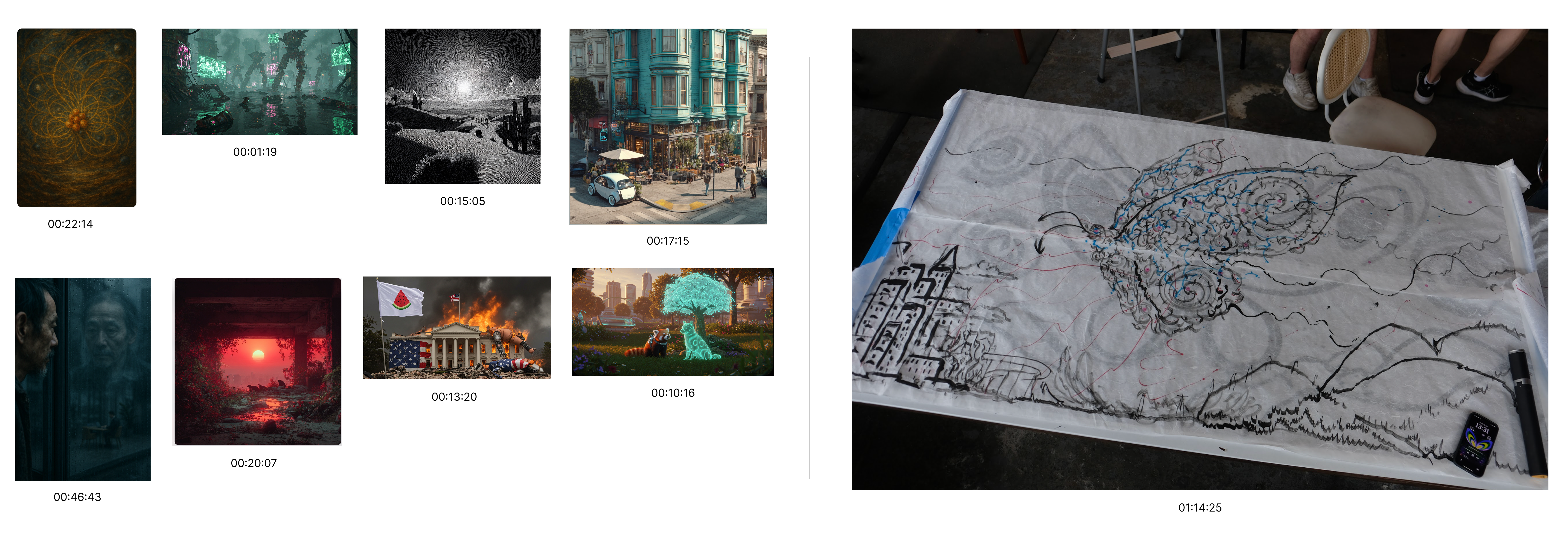

For simplicity of comparison and based on the accessibility of available tools, the pilot for Labor (Revealed) begins with a focus on illustration as a performance and a workshop, where a professional illustrator and eight participants are invited to explore the idea of the performance. The artist is chosen based on their professional title as a practicing artist in illustration, whereas the participants are selected through snowball sampling from the creative community associated with the space where the pilot workshop was held. In this iteration of the pilot, the illustration artist creates a live ink painting alongside the participants, who are tasked with executing a creative brief. Participants interacted with three devices featuring widely used and accessible commercial text-to-image models: Imagen, GPT-4o, and Midjourney. These tools were selected because of their affordability, accessibility, and user-friendly interfaces, which require minimal technical expertise and setup. The artist and participants are given the same creative brief: “A vision for the future.” This was intentionally left neutral, neither overly pessimistic nor overly optimistic, to allow the audience and artist to interpret the vision of the future using AI tooling.

After participating in the pilot, a collective discussion was held, and qualitative data were gathered through a survey to better understand the participants’ experience and perception after the performance. A thematic analysis revealed a diverse group of participants with some working in the creative field, including those with varying levels of experience with creative AI tools. There’s a mix of skeptics and optimists in the group, but as a whole, they lean negative in their perception of AI technology. The hope is that in the future iteration of the installation, the diverse perspectives of artist practitioners who use AI and those who do not will be captured in the performance and subsequent qualitative research.

The workshop culminated in a display of the artist's complete works, alongside those of the participants. Each work has a timer next to it showcasing the amount of physical creative labor required for each output. While this juxtaposition highlights the time-value disparity between humans’ physical labor and AI labor, there is so much that is also left invisible, such as the “immaterial labor” of the artist, as well as all the labor that went into the creation of these AI systems, hidden behind the facade of the machine. However, regardless of this visibility, it has already affected the perceived value, as most participants preferred the artist’s piece due to their appreciation for the visualization of the process. As one participant noted, time does affect the artifact because the AI-generated artifacts were so easy to create, they almost felt cheap (Participant 6, survey).

The AI outputs created a perceived absence of human emotion and narrative despite each participant and artist being asked to describe their creative process and intention behind their work. The invisibility of the labor that went into the creation of the model allowed participants to accomplish their goal much quicker than the physical artist, whose work was visible and apparent in the duration it took to complete the painting. The physical artist took one hour and fourteen minutes, while the participants' times ranged from one minute and nineteen seconds to forty-six minutes and forty-three seconds.

The invisibility of the AI model labor, in contrast to the visibility of the artist's physical labor, contributes to the perception of value in the final outputs, influencing preferences. Despite having created their own AI output themselves, most of the participants prefer the physical artist’s work. As noted by a participant, I appreciated [the artist’s] creative process more than the automated, generic AI-assisted artifacts where it’s a black box (Participant 4, survey). The black box reference directly highlights the invisibility of the immaterial labor that went into the creation of these AI, as the participants cannot see the visible labor that went into the creation of the model—they can only see their own labor that went into the output. Compared to the highly visible, time-consuming labor of the physical artist on the other side, it is easy to perceive the labor as more valuable in contrast to the cheapness of the AI output that may be perceived as lower effort—a common perception of AI slop.

The design of the installation prompts questions that arise during my practice-based research, and I became interested in whether artists are creating with AI, how they do it, and how the inclusion of AI technologies affects the value perception of the pieces' outcomes. It led me to consider the following research questions:

In the pilot performance, the sample size of participants is small, which may not represent the general population. These individuals have more experience with AI technology than average, and the group's sentiments are skewed negatively towards AI technologies. Most individuals had a positive perception of the performance and preferred the artist’s live production of work. As a whole, the group felt that visualizing the artist’s performance and listening to the artist's explanation allowed the work to resonate more with the participants as they appreciated the layered meaning behind the live painting. To quote a participant, they felt that creating with AI feels inconsequential: I tend to have little emotional connection to what I make/made, and in many ways, it feels like I didn't create it. Because there is little sacrifice in creating AI-generated artifacts, it's hard for it to feel valuable (Participant 6, survey).

Across the group, participants who engaged with AI generation consistently preferred the artist's interpretation and live performance over their own AI-generated outputs. This sentiment is encapsulated by one participant: I think some of the images were okay looking, but lacked the feeling and thought of the physical work (Participant 5, survey).

In an interview with the illustration artist Jeremy Leung, his design philosophy centers on explicitly and intentionally avoiding the use of AI in the final output, despite sometimes employing it as a brainstorming tool in the conceptual phase. Leung describes AI art is not art because you aren't going through the labor to generate that image or images. He believes art is the making of it, too…the process of composing [it is] what makes art, art. And if you're just giving it to an algorithm to generate, then it's a hollow shell of what art is (Leung 2025). Leung's perception of AI represents one perspective, but these perspectives may differ across industries and media. AI affects illustration differently from other media, like music creation or physical sculptures. Future iterations of this work will expand on the diversity of perspectives with the creative domains, hoping to capture the diverse points of view of other artists and creators.

For future installations, I plan to conduct additional ethnographic research with participating artists to understand their relationship with AI technology in addition to gathering more qualitative feedback from participants and viewers to explore their sentiments on AI's impact on creative labor, aiming to foster conversation during the installations. This method employs exhibition-based research methods to close the research loop of understanding the effects of an exhibition on its viewers by capturing the moment in time sentiments and reactions of the audience members with the piece of work and their relationship with either interacting with it or viewing it (Eccles et al, 2024). Oftentimes, the immediate response to a piece leaves with the audience as they leave the exhibition. I’m interested in understanding the audience’s and participants’ reaction to AI labor vs. human labor, their understanding of the tradeoff between time, labor, and creativeness of the final output, as well as their sentiments around visualizing what is typically invisible in the creative process–the time and the process.

Labor (Revealed) explores the complex relationship between AI, creativity, and human labor through the lens of performance and installation art. It engages audience participation and questions our perception of value creation and generation in the context of AI technologies versus physical human labor. It acknowledges the visibility and invisibility of the cognitive and physical labor that goes into the creation process and intends to lead us to question, critique, and reconsider the impact of AI on creative labor. Its design is meant to be malleable and can evolve with the research process.

Future iterations will advance this research-based practice into an installation art series, eventually exploring all creative domains and artistic perspectives on AI’s impact in the creative field. It aims for a larger, more diverse sample size, ensuring balanced perspectives of AI optimists and skeptics, as well as formalizing a comparative analysis across different creative disciplines through performances on a diversity of media such as music and sculpture. Through the process of refining the installation series, I’m looking to develop and discover additional research questions within the domain of Human-AI interactions and the value perception of creative labor in creative outputs, including touching upon some of the ethical issues around copyright infringement that may contribute to the perceived value of a creative output. Even amongst artists, there are a lot of strong conflicting opinions and viewpoints on the field of AI and art, which is an emerging field that is profoundly affecting the creative community today.

1) Katz, L. (2024, December 15). Google challenges artists to defy AI cliches, with striking results. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/lesliekatz/2024/12/12/google-asks-artists-to-defy-visual-cliches-of-ai-with-striking-results/

2) Kozanecka, E. (2024, December 12). 3 artists reimagine AI imagery through speculative photography. Google. https://blog.google/technology/ai/3-artists-reimagine-ai-imagery-through-speculative-photography/

3) Chung, Sougwen. 2015-present. D.O.U.G., Victoria and Albert Collection; London.

4) Reben, Alexander. 2020. AI am I? https://areben.com/project/ai-am-i/

5) Braverman, Harry. Labor and Monopoly Capital: The Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1974.

6) Tyler Hobbs, "Tyler Hobbs," in The Work of Art: How Something Comes from Nothing, by Adam Moss (New York: Penguin Press, 2024), (312-317).

7) Mario Klingemann, "The Pixels Themselves: An Interview With Mario Klingemann," The Quietus, last modified September 18, 2019, https://thequietus.com/culture/art/mario-klingemann-ai-art-interview/.

8) Philip Galanter, "What is Generative Art? Complexity Theory as a Context for Art Theory," paper presented at the International Conference on Generative Art, Milan, Italy, December 2003. https://www.philipgalanter.com/downloads/ga2003_paper.pdf.

9) Winter, A. (2023, November 13). The SAG deal sends a clear message about AI and workers. Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/hollywood-actors-sag-artificial-intelligence-contract/

10) Boden, M. A., & Tony Bruce. (2004). Creative mind: Myths and mechanisms. Routledge.

11) Steyerl, Hito. "Mean Images." New Left Review, no. 140/141, Mar.-June 2023.

12) Lazzarato, Maurizio. "Immaterial Labor." In Radical Thought in Italy: A Potential Politics, edited by Paolo Virno and Michael Hardt, 133–47. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996.

13) Pasquinelli, Matteo. The Eye of the Master: A Social History of Artificial Intelligence. New York: Verso Books, 2023.

14) Cohen, Harold. 1979. "What Is an Image." Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence 6: 1028–37.

15) Harold Cohen: AARON. Exhibition. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, February 3–May 19, 2024.

16) Becker, Howard S. Art Worlds. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982.

17) Eccles, K., Herman, L., Moruzzi, C., & Mustaklem, M. (2024). Introducing the method of Exhibit-Based Research. Communication Design Quarterly. Advanced online publication. https://doi.org/10.1145/3627691.3627696

18) Jeremy Leung, interview by Shirley Leung, Brooklyn, NY, July 16, 2025.

19) Qualitative survey of 7 participant members, Shirley Leung's research project on AI and creativity, July 2025.