This developing project explores the conspiracy theory about fake birds, specifically pigeons, in relation to modern computing. Ubiquitous computing is one of key moments in computing history, emphasizing invisibility and omnipresence in the design of computational processes. This perception has influenced the development of modern technology such as the Internet of Things (IoT), and the urban myth about pigeons seems to share similarities with it. The development of computational processes and the domestication of pigeons also have proximity to authoritarian operations. The project aims to develop a speculative design artifact that investigates the practice of imitating animal forms and dissolving computational processes in the background.

Technology and Society, Ubiquitous Computing, Surveillance, Biomimetics

In a small corner of the online world, there are people gathered around fake birds. The Reddit community called “birds aren’t real” has more than 500,000 followers. The users entertain the idea of birds being secretive drones employed by the government by posting contents of suspicious or silly birds. (“Birds Aren’t Real,” n.d.) The website Pigeons Aren’t Real contains information about a conspiracy theory that features pigeons as government surveillance devices. (“Pigeons Aren’t Real » The Truth about Government Surveillance Drones” 2020) Even though a lot of them aim to be satire and humor, it is a peculiar way to perceive biological beings as covert operation machines. What are the relevant technological developments to fake birds, and what does that tell us about the relationship between technology and society?

This study explores the relationships that humans form with animals and technology by finding links between modern computational processes and urban conspiracy theory through a sociopolitical lens. The paper argues that pigeon surveillance conspiracy represents the social perception toward ubiquitous computing and its abuse. To investigate, the paper explores two layers of context regarding this urban myth. In the first part, the paper looks for the reason behind the biomimetic facade of such imaginary pigeon machines. The study suggests that pigeons are seen as surveillance machines because humans have a history of exploiting animals in history which led these urban animals to become expendable and are ignored in the modern era. Secondly, this project questions the seemingly innocuous technology and its potential social influence. Then lastly, the study proceeds to relevant creative practices.

RQ1. Why mimic a certain biological species for authoritarian technology use?

RQ2. What are the relevant technological developments to fake birds, and what does that tell us about the relationship between technology and society?

RQ3. Is there a way to re-imagine ubiquitous computing?

This paper gives a nod to material culture studies as a method, doing an interdisciplinary study to see how the culture surrounding surveillance pigeons was established. Similar to material culture scholar’s investigation on the notion of hygiene through advertisement and sanitization products, this project also seeks a diachronic stream around the fake pigeons. (Forty 1986) Difference is that in this case, the artifact is imaginary rather than an existing object. Also, the project chases after a conspiracy theory, which is a cultural byproduct that is not believed to exist. Hence, the approach for this project may refer to material culture studies, but not entirely. While borrowing the aforementioned method, this paper also refers to critical theoretical concepts in media theory. The next part creatively contemplates on creating a speculative artifact that critically examines the idea of ubiquitous computing and its applications along with biomorphic forms.

Identifying the cultural and historical context of an object contributes to understanding of the artifact. This project expands and also diverts slightly from material culture studies to provide possibilities of applying such approach to modern technologies and other subjects. Also, the concepts from media theory that appear in this paper have original authors to provide many examples of the era when the writings were done. It is anticipated to broaden such discussions by applying the theoretical framework to current media. Speculative design as a method sees design artifacts as “...intentionally crafted to encourage reflection on how technological devices and systems shape (and often constrain) people’s everyday lives, behaviors, and actions in the world” including satirical objects and radical design. (Wakkary et al. 2015; Dunne and Raby 2024) By imagining speculative objects, the project provides an opportunity to think critically and different from conventions. The artifact for this project, Poopy Pigeon, functions as a satire and also a question on how people develop and perceive biomorphic machines. Additionally, creative practices have potential to make discoveries during its process, which is also a goal and contribution of this project.

Let’s start with the first point – why pigeons? An interesting aspect of pigeon conspiracy theory is that they are not suspecting cell towers, traffic cameras, or street lamps, which are common artificial objects. Why does a machine imitate a creature with flesh and bones? The theory of fake birds is entertaining partially because it is unrealistic. Mass-producing such sophisticated machines requires a lot of resources, and it is not more than a theory that those exist. Common imaginary schematics of fake birds comprises camera, network device, and other electronic components for spying. Considering the anatomy of living organisms are often invisible and ambiguous, it might make sense that people speculate those animals with mysterious mechanical interiors, similar to when people perceive advanced modern technologies – an unseen and complete black box. (Latour 1988) In addition, scholars like Kapp argued that technology eventually mimics biological structure. (Kapp 2018) There is also Jacques de Vaucanson’s automaton, “Digesting duck” from the 18th century. (Bosak-Schroeder 2016) Imagining animals including humans as a machine is not novel, but pigeons seem to have a closer connection with technology in history.

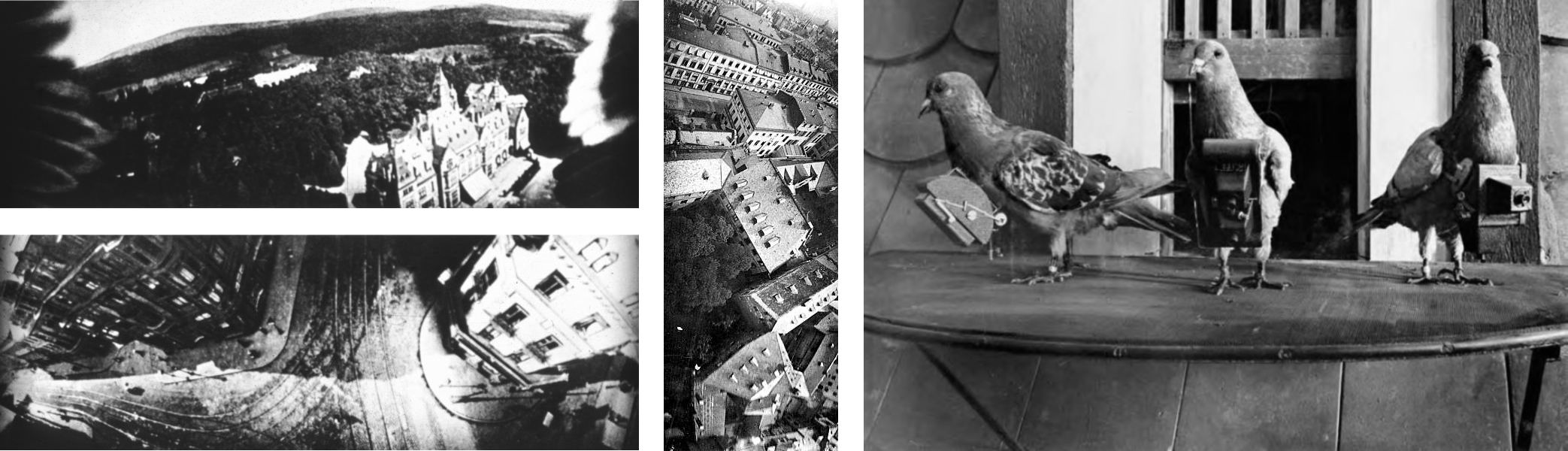

Pigeons are a commonly recognized bird in many regions around the world, despite the difference in density. Historically, pigeons have been employed by humans for a long time. These little birds roam around many urban cities in North America, South Asia, and more. The human interest in pigeons started early on. Notably, Charles Darwin was very passionate about them. In his book which was published later than the Origin of Species, Darwin dedicated an individual chapter to pigeons. He argued that the pigeons we see nowadays started from one kind, Rock Pigeon (Rock Dove; Columba livia). (Darwin, n.d.) During the war in the western world, pigeons held a crucial role in distanced communication. Soldiers and troops deployed homing pigeons from remote bases to relay classified messages to the home base. One of the most famous of the kind is Cher Ami, a homing pigeon that received a medal from France post World War I for its dedication. Pigeons were primitive networked devices for data transmission. Cameras were mounted on these little birds to get an image from above, which resembles the function of a modern drone. In 1907, a German inventor Julius Neubronner submitted a patent of a miniature pigeon camera activated by a timing mechanism. (Fig. 2.) In 2024, a pigeon was arrested and detained in India, being accused of espionage. The alleged spy pigeon was under investigation for 8 months before being released. It was not the first time these creatures were accused of crimes. (The Associated Press 2024) This unfortunate event is related to the history of pigeons working close to the military and intelligence services formed a specific perception and reputation of them, which remains to this day. Considering this, imagining fake pigeon agents eavesdropping on us does not seem farfetched.

Ubiquitous computing is one of the memorable moments in computing history. The concept is also known as pervasive computing, and it is recognized as the third major movement of modern computing to some scholars. (Krumm 2009; Dhingra and Arora 2008) It is also considered as the root of IoT (Internet of Things) sometimes. (Macaulay 2015; Tinnell 2023) The term was started by Mark Weiser while he was at Xerox PARC (Palo Alto Research Center) in the United States, and later he developed the concept of ubiquitous computing into calm computing until he passed away. The Computer for the 21st Century written by Weiser in 1991 positions it as a critical piece that first laid out the idea of ubiquitous computing. The article presents the development of interconnected pads (adjacent to modern tablets) and badges at Xerox PARC as examples. Weiser did not focus on having the user's attention onto the screen, rather, he wanted to make “things” disappear. What he envisioned was a highly integrated system, as he also introduced the concept, embodied virtuality. (Weiser 1991) The most important aspect of ubiquitous computing to him was invisibility. (Weiser 1994) Now, omnipresence also has significant meaning in ubiquitous computing. (Gajjar 2017) In summary, the concept anchors on making networked devices unnoticeable and present everywhere. The idea of ubiquitous computing started in the late 80s as an internal program at Xerox PARC and the Computer Science Laboratory (CSL) when they were working on LiveBoard, ParcPad, and ParcTab which was funded by DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency).

We wanted to put computing back in its place, to reposition it into the environmental background, to concentrate on human-to-human interfaces and less on human-to-computer ones. (Weiser, Gold, and Brown 1999)

As Weiser intended to blend computing in “environmental background,” Invisibility and omnipresence were mostly implemented to modern computing in home IoT devices and urban infrastructure. Ubiquitous computing intended to minimize human involvement on the users’ end and hid the computational processes under the surroundings. Nowadays, the seamless access to technology through the network has become a familiar idea in the places that can afford such technology. Dissolving computational processes into the background of our lives resulted in an interesting perception: Everything everywhere has a potential to be a technological artifact.

Obscuring techniques applied on computing brings up the question of privacy. By suggesting the capture model, Agre argues implemented computations captures data and leads to surveillance. For instance, employees tagging badges and goods being processed in distribution centers don’t seem to be actively monitored. However, concealing the data transfer rarely alerts the users about collection and storage of accumulated data. (Agre 1994) The artifacts developed by Xerox PARC that opened the era of ubiquitous computing proves this exact process, such as the badge sending information on the holder’s location. The nature of ubiquitous computing creates a wiggle room for privacy manipulation. Invisibility and omnipresence happen to be the strong values for surveillance as much as it is providing convenience to people.

Pigeons were domesticated for various purposes over time other than communication. They were bred and kept to produce fertilizer for agriculture. Also, pigeon racing has been going on all over Europe and Asia. (Mosco 2021) Some scholars claim that feral pigeons we now see and identify originated from escaped domesticated ones. (Johnston and Janiga 1995) Now, as a result of heavy domestication, pigeons are everywhere. They however, are considered as outdated technology, and earned a dishonorable nickname, “flying rats.” (Malamud 2013) Similar to ubiquitous computing, pigeons are omnipresent and invisible. In urban environments, these little critters became a part of the background. As their nickname implies, pigeons are disdained and ignored as they are very common. This unique position that pigeons acquired in modern society resembles ubiquitous computing. The paranoia towards highly surveilled cities and discreet hidden technology are embodied in urban pigeons. Also, utilizing non-human animals as a facade for secret operations does not only apply to pigeons. One of the examples is Dead Drop Rat. During the Cold War, the CIA (Central Intelligence Agency) used to conceal secret messages inside of a dead rat, sew it up, and drop it to designated locations to communicate. (Central Intelligence Agency 2020) Due to the negative implications of dead rats related to diseases and pollution, it was considered as an effective method of information transfer since people refused to get close. Also, rats are omnipresent invisible urban animals like pigeons. Strategies such as this one bear similarities to the pigeon conspiracy theory – using common animals that are easily ignored to conceal something.

Barthes argued that technologies and artifacts bear concealed ideological context, which he explains through a concept of “myth.” (Barthes 2012) Thinking of ubiquitous computing, the myth can be a notion that such technology only exists to benefit but in fact, its development is closely related to authoritarian usage. The myth can also appear as a narrative of providing security to the public while the tracking does not always apply to malicious events. The fake bird theory, or a surveillance pigeon conspiracy, seems to present itself as a counter measure to such myths. This project sees this humorous imaginary suspicion as a reactive narrative from the controlled one led by the authority. Hence, an ecosystem of myths is formed and shared based on the same technology, but on the pigeons’ bodies.

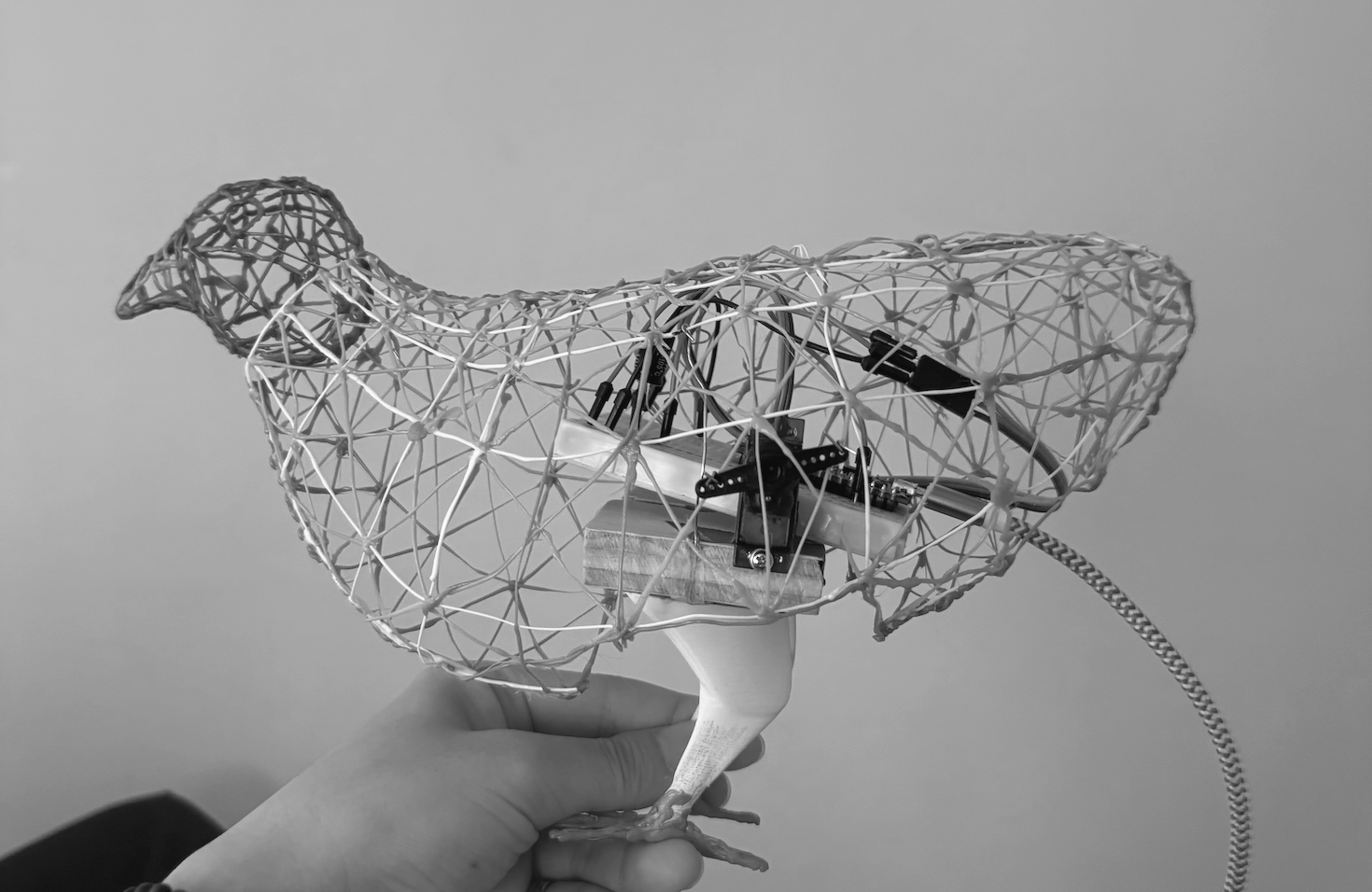

The creative practice started as building a prototype of a pigeon agent. It started with a speculation on which functions will be included if someone makes a surveillance pigeon robot with a serious intention. Most existing pigeon conspiracy schematics on the web describe the birds to have parts for utilities only. However, if the machine only focuses on input devices and network functions, it is highly unlikely that the pigeon blends in with the surroundings. Among many distinct features that pigeons have, defecation seemed most suitable and obvious behavior to mimic even though it is uncommon to make an artifact that performs the action. Also, by creating such mischievous artifact functions as a satire, which is one way of re-imaging the ubiquitous computing and surveillance from it. To ridicule and start a conversation on how people decide to utilize certain technology, this speculative artifact only exists for defecation. The lack of utility rejects the idea of almighty avian robots, but instead, imagines the natural biological species performing one of the fundamental organic processes.

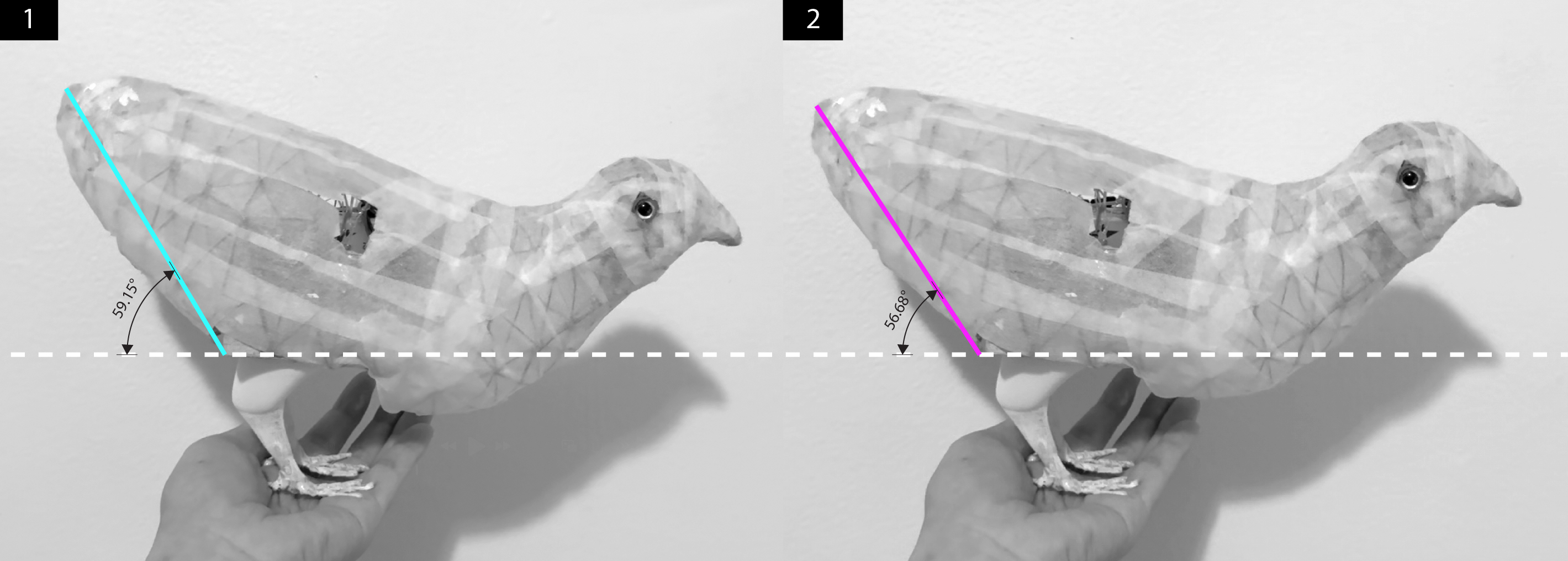

The process started with observing and analyzing discharging motions of pigeons and other birds from outside. During the initial phase, most of the research was dedicated to identifying the major characteristics of such action. Based on the observation, the key movement for pigeons to engage in bowel movement was a tilting motion. Most of the birds become idle for a short period of time, then lift their rear ends to start defecation.

To create the exterior of the prototype pigeon, a 3D model was created to be printed with PLA material. (Fig. 3.) The total length of the model is about 30 cm, considering the average size of pigeons runs between 30~34 cm. Post-print, the prototype’s rigid body was not suitable to house the components inside and the stiffness of the material did not resemble life forms. To troubleshoot, a netted-form enclosure was made with PCL, which is more flexible and squishy than PLA. (Fig. 4.) The legs were the only parts that remained as PLA print since the part required strengths and stability.

To incorporate the main movement, the pigeon moves by a servo motor to imitate the tilt. The circuit is powered by one 9V Lithium-ion battery and the microcontroller used in the prototype is Arduino Nano BLE 33. Considering that this is an autonomous entity, there is no external input to control the bird to defecate on command. The movement happens randomly. The bowel movement happens based on the tilting motion. When the bird lifts its tail, the rubber tube inside of the bird hinges and the feces, which is a white color high-flow acrylic paint, runs down.

The first version of the prototype raised three issues that needed improvements. Most of the major issues came from hardware. Firstly, the legs required a connecting part that was rigid enough to put the board on and also attach the tube to hinge. A thick wooden panel supported the components in the version 1. The wires connected to the panel and the attached section were not stable. One solid body for such parts should be printed as a whole in the second version. The second issue was that the rotating degree was hardcoded as 20°. However, due to a flexible enclosure, the motor’s rotation angle was not fully transferred to the exterior. The final tilt came out to be 3° (± 2, depending on the baseline). (Fig. 5.) An additional part or leverage should be applied to enhance movement. Lastly, a larger storage for the feces (acrylic paint) and a more realistic depictions with solid materials inside the runny substance are required.

The paper focused on how modern day conspiracy theories and culture perceive animals as a representation of invisible computational processes and surveillance. Throughout the paper, the project explored how fake birds, especially surveillance pigeon conspiracy theory, reflects the perception of biological species and invisible computational processes through form and content, which each responds to RQ1 and RQ2. This project took a speculative and satirical approach for RQ3 and created a pigeon robot that performs unexpected tasks powered by modern technology. Moving on from hitherto discussion on pigeon agents, the next steps of the project are twofold. On the theoretical side, the implications of employing biomimetic form potentially can be expanded by exploring media theories further. The current study mostly focuses on identifying and examining the current phenomenon. Future research is expected to include broader theoretical discourse. Regarding the practice, the current artifact has limitations in covering the complicated discussions. For instance, the satirical approach lacks attention on discovering the design intentions of biomorphic robots. To enrich the context artifact brings and to reflect theoretical layers more thoroughly, the project is planning to create a series of different artifacts in addition to Poopy Pigeon. Also, how to display or deploy and research further with the artifact needs more considerations.

Agre, Philip E. 1994. “Surveillance and Capture: Two Models of Privacy.” The Information Society 10 (2): 101–27.

Barthes, Roland. 2012. Mythologies. Translated by Richard Howard and Annette Lavers. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

“Birds Aren’t Real.” n.d. Accessed February 16, 2025. https://www.reddit.com/r/BirdsArentReal/?rdt=33846.

Bosak-Schroeder, Clara. 2016. “The Religious Life of Greek Automata.” Archiv Für Religionsgeschichte 17 (1): 123–36.

Central Intelligence Agency. 2020. “The Debrief: Behind the Artifact - Dead Drop Rat.” Youtube. October 7, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X1rhb8J2cCk&t=45s.

Darwin, Charles. n.d. “The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication.” Project Gutenberg. Accessed February 10, 2025. https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/3332.

Dhingra, Vandana, and Anita Arora. 2008. “Pervasive Computing: Paradigm for New Era Computing.” In 2008 First International Conference on Emerging Trends in Engineering and Technology, 349–54. IEEE.

Forty, Adrian. 1986. Objects of Desire: Design and Society since 1750. London, England: Thames & Hudson.

Gajjar, Manish J. 2017. “Context-Aware Computing.” In Mobile Sensors and Context-Aware Computing, 17–35. Elsevier.

Johnston, Richard F., and Marian Janiga. 1995. Feral Pigeons. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Kapp, Ernst. 2018. Elements of a Philosophy of Technology: On the Evolutionary History of Culture. Edited by Jeffrey West Kirkwood and Leif Weatherby. Translated by Lauren K. Wolfe. University of Minnesota Press.

Krumm, John, ed. 2009. Ubiquitous Computing Fundamentals. Philadelphia, PA: Chapman & Hall/CRC. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781420093612.

Latour, Bruno. 1988. Science in Action: How to Follow Scientists and Engineers through Society. London, England: Harvard University Press.

Macaulay, Tyson. 2015. RIoT Control: Understanding and Managing Risks and the Internet of Things. Oxford, England: Morgan Kaufmann.

Malamud, Randy. 2013. Trash Animals: How We Live with Nature’s Filthy, Feral, Invasive, and Unwanted Species. Edited by Kelsi Nagy and Phillip David Johnson. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Mosco, Rosemary. 2021. A Pocket Guide to Pigeon Watching: Getting to Know the World’s Most Misunderstood Bird. London, OH: Workman Publishing.

“Pigeons Aren’t Real: The Truth about Government Surveillance Drones.” 2020. Pigeons Aren’t Real. April 28, 2020. https://pigeonsarentreal.co.uk/.

The Associated Press. 2024. “Flight Risk: Suspected Spy Pigeon Released after Eight Months in Detention in India.” The Guardian, February 2, 2024. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/feb/02/india-spy-pidgeon-suspect-china.

Tinnell, John. 2023. “The Philosopher of Palo Alto.” University of Chicago Press. pu3430623_3430810. May 2023. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/P/bo194495767.html.

Wakkary, Ron, William Odom, Sabrina Hauser, Garnet Hertz, and Henry Lin. 2015. “Material Speculation: Actual Artifacts for Critical Inquiry.” Aarhus Series on Human Centered Computing 1 (1): 12.

Weiser, Mark. 1991. “The Computer for the 21st Century.” Scientific American. September 1, 1991. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-computer-for-the-21st-century/.

———. 1994. “The World Is Not a Desktop.” Interactions 1 (1): 7–8.

———. 1994. “Creating the Invisible Interface: (invited Talk).” In Proceedings of the 7th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology - UIST ’94. New York, New York, USA: ACM Press. https://doi.org/10.1145/192426.192428.

Weiser, Mark., R. Gold, and J. S. Brown. 1999. “The Origins of Ubiquitous Computing Research at PARC in the Late 1980s.” IBM Systems Journal 38 (4): 693–96.